The Adirondack mountains remained largely untrodden until Professor Ebeneezer Emmons from Williams College decided to climb Mount Marcy in 1837 during his geological survey of Northern New York issued by NY state (Waterman 106). Although Emmons advocated for people to explore the park, his expedition did not catalyze the development of trails in the Adirondacks. Emmons climbed up mountains, but he did not create true trials which are defined as “partially cleared, not merely blazed” (Waterman, 111).

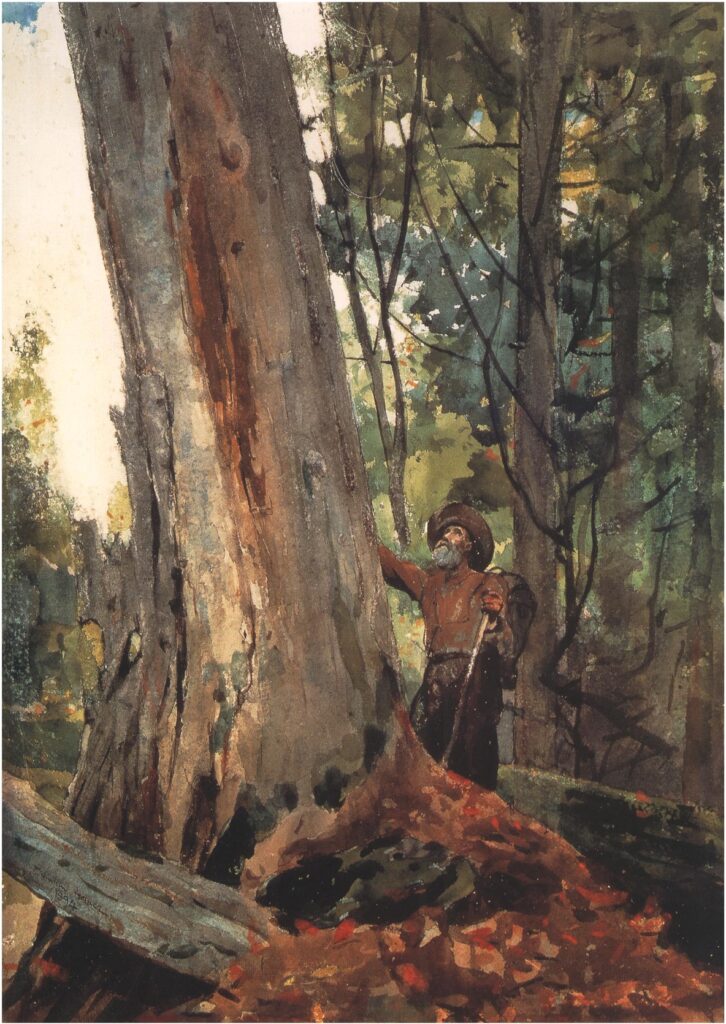

Guides were the group of men to create the first real trails in the Adirondacks. These were local men who assisted visitors like Emmons and wealthy tourists looking to explore the wilderness of the park. Given their year-round residence in the Adirondacks, guides had an abundance of knowledge on how to survive in the wild. Not only did they know how to set up camps, find the best fishing spots, and pack everything tourists would need, but they knew the best routes to climb mountains. As popularity of the Adirondacks grew among the wealthy elite, they cut official trails to summits to make it easier to lead groups up to the views they wanted to see.

Orson Schofield Phels, or “Old Man Phelps” was a prominent figure in bringing hiking to the park. He was part of Emmons group that ascended Mount Marcy, and he was the guide who cut the first real trail up Mount Marcy from the Keene Valley in 1845. Phelps joined Verplanck Colvin’s exploration of the park in 1837, helping him ascend Mount Colvin and Skylight. Eventually, he would go on to cut the first Marcy-to-Skylight trail in 1875. He was the most popular guide for visitors to travel with from 1850 to the 1870s, and he spent a lot of time developing real trails in the mountains by Kenne Valley where he lived (Waterman, 166).

Other prominent trail-building guides include Andrew Hickok, Bill Nye, and John Cheney. Hickok cut the first formal mountain trail to the top of Mount Whiteface in 1859, and Nye was credited with clearing the first route from Lake Placid to Whiteface’s peak during the year 1865 (Waterman, 66 and 165). These trials would go on to be further developed once bigger organizations got involved in trail development, but the very first trails were most often constructed by individual men.

Guidebooks

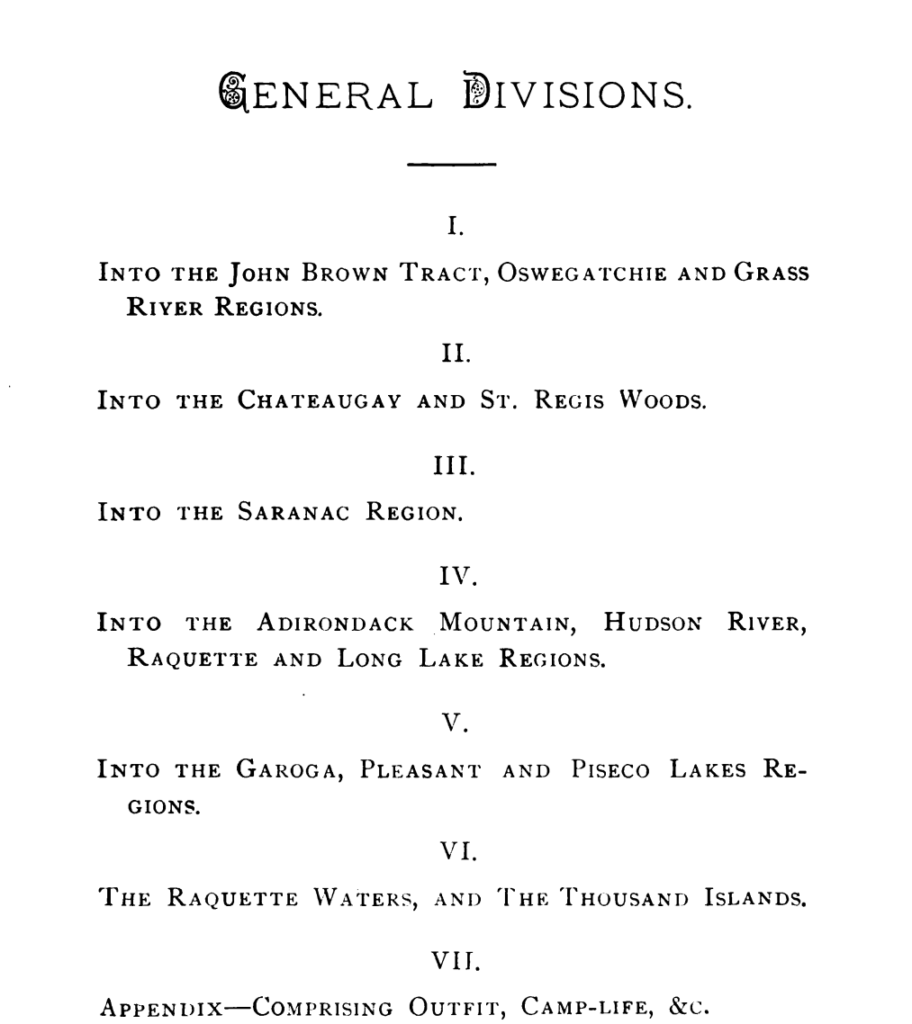

The guidebook was the final nail in the coffin for the park’s guides. These books play a huge role in the history of trail building in the Adirondacks since they listed and described the trails that they either created or were familiar with for readers. Edwin R. Wallace’s Descriptive Guide to the Adirondacks was a popular guidebook among Adirondacks vacationers, and he updated it annually beginning in 1875 (Waterman, 195-196). It divided the park into different sections, detailing where to find scenic routes and describing the trails for tourists so they stayed on track.

Source: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015020105246&view=1up&seq=5

These books gave visitors all the information they needed to make their own way in the Adirondacks. As a result, guides became less popular and the mysticism of the park that guides represented faded away (Waterman, 144). A need for economic expansion and material gains became the focus in the park, and the hiking industry changed forever.